An Anthology: The Evolution of Jekyl Island through 1930 4,860 Word Count, 16 Min Read Time, 54 Images

7 November 2023

Updated, 9 October 2025 with edits for clarity, image links and addtl. info on the wharfs and boathouses

Linked Index

- Overview of Sanborn Maps

- Evolution of Jekyll Island Historic District

- The 1890’s

- April 1893

- July 1898

- The early 1900’s

- June 1908

- July 1920

- The 1930 Survey Map

- 1920 Survey Map Composite

- Other Maps For Points of Reference

- Places Lost to History

- The Brick Outlines in the Historic District

- The First Owners of the Club Apartments

- More about the Sanford Fire Insurance Maps

Overview of Sanborn Maps

For those who have never heard of nor seen a Sanborn Fire Insurance Map, there is an excellent, detailed “article “hosted on the Library of Congress’ researcher Geography and Map Reading Room entitled “Introduction to the Sanborn Map Collection”. It outlines their history, purpose as well as the history of the company and provides insight into the legends used on the map and how to properly use the ‘fire insurance’ maps from the collection that can also be found in other educational and state government archives.

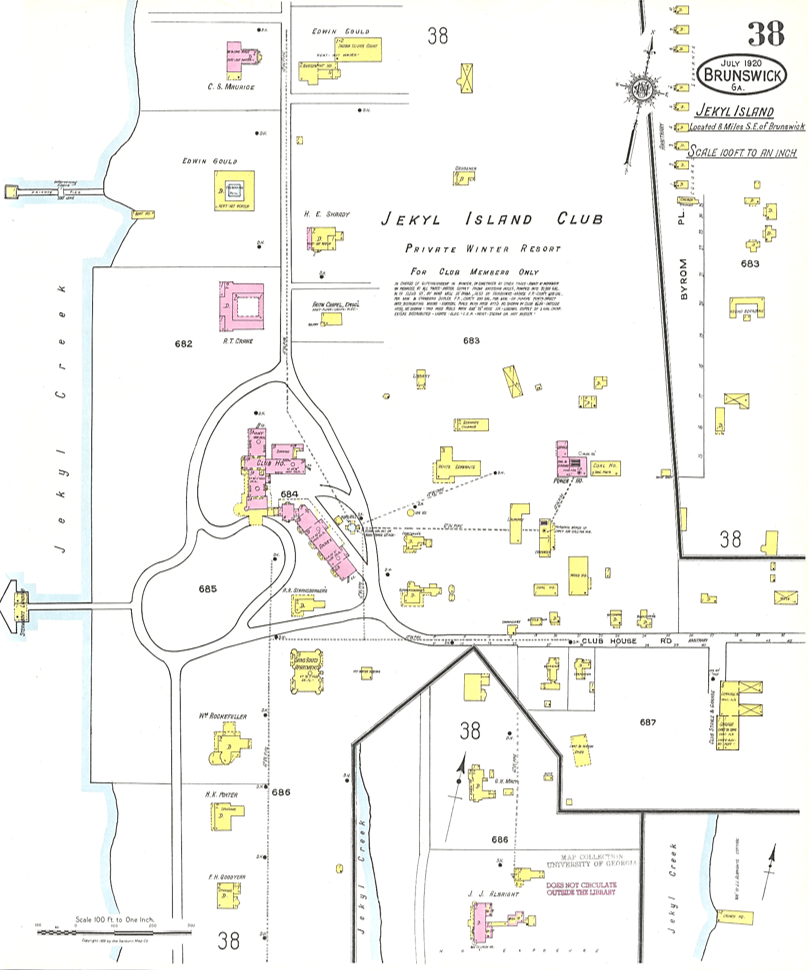

Like most major counties and cities in Georgia, Glynn County and Brunswick Georgia enlisted the Sanborn Map Company to prepare a series of fire insurance maps beginning in the late 1800’s. It would appear Jekyl Island’s key structures were included in the Sanford surveys conducted and published for the City of Brunswick as it was the county-seat of Glynn County and likely had jurisdiction over the island due to proximity and to which it was host to the primary ferry service for the island.

In my searches, I was able to locate on-line, scanned Images of four of the five Maps produced for the City of Brunswick that included some of the structures on Jekyll Island for the years 1893, 1898, 1908 and 1920. There is a fifth that was apparently produced for 1930, but images of it are no longer visible on-line through any of the available resources that I’ve discovered.

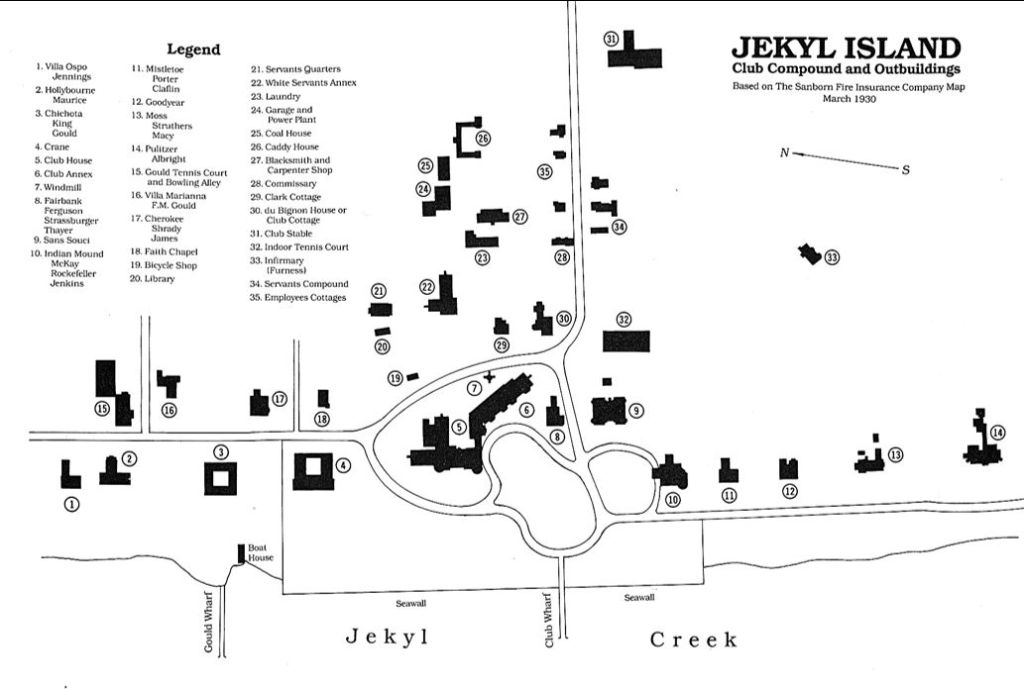

However, a facsimile was produced by someone that is included in William and June McCash’s book The Jekyll Island Club and also cataloged at Wikipedia that I’ve included, at right. However, as you’ll see below, the actual maps are far more detailed in many respects, while still omitting a lot of information on structures that were likely not of concern to the insurance companies or the cities that had to support fire services to insurance subscribers.

The Evolution of the Jekyll Island Historic District from 1893 to 1930 based on Sanborn Fire Insurance Maps

The following is a collection of original images, many of which I’ve annotated to make them easier to understand and have also added additional legends and notations regarding omissions such as the Brown and Furness Cottages, and changes since the 1930 map was produced, e.g., the loss of the Chichota, Fairbank and Pulitzer cottages. Most importantly, I’ve created a composite image of the Historic District to illustrate proper alignment of the 1920 Sanborn Fire Insurance Map’s insets for the five (5) club member cottages located on the South end of the Historic District, as well as the club’s ‘colored servant district’ also know as ‘Red Row’ that was located at the North end of the Historic District. The latter is the key to putting the original layout of the Jekyl Island Club structures in their correct placement at the time the Sanborn Map Company based in New York performed the four survey map sets I was able to locate.

The 1890’s:

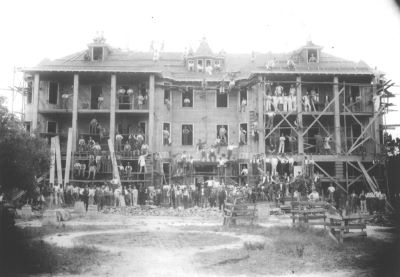

- April 1893: The first survey map from April 1893 was published eight-years after the founding of the Jekyl Island Club in December 1885 and construction of the clubhouse and several other primary structures. It clearly illustrates the close-in clubhouse district with the original, much smaller clubhouse and only shows two of the six club member cottages — the McKay and Fairbank Cottages– that had been built by the end of 1892. To the south of the clubhouse it also shows the 1884 DuBignon house in it’s original location, prior to being relocated in 1896 to allow for the construction of the San Souci apartments. The Brown Cottage located northwest of the clubhouse and main club compound area nor the Soltera, Hollyborne or the Furness Cottages and other structures that — and this is only a guess — were neither insured nor close enough to insured properties to warrant inclusion in the survey map set for Brunswick.

The lower-right of the drawing reflects what appears to be the produce gardens & club-owned structures to the southeast of the clubhouse, to include two dwellings (C2) as well as what are shown as the club stables. It may be that these are the original stables — something I still need to investigate — as new stables further to the east of the club compound were built in 1897.

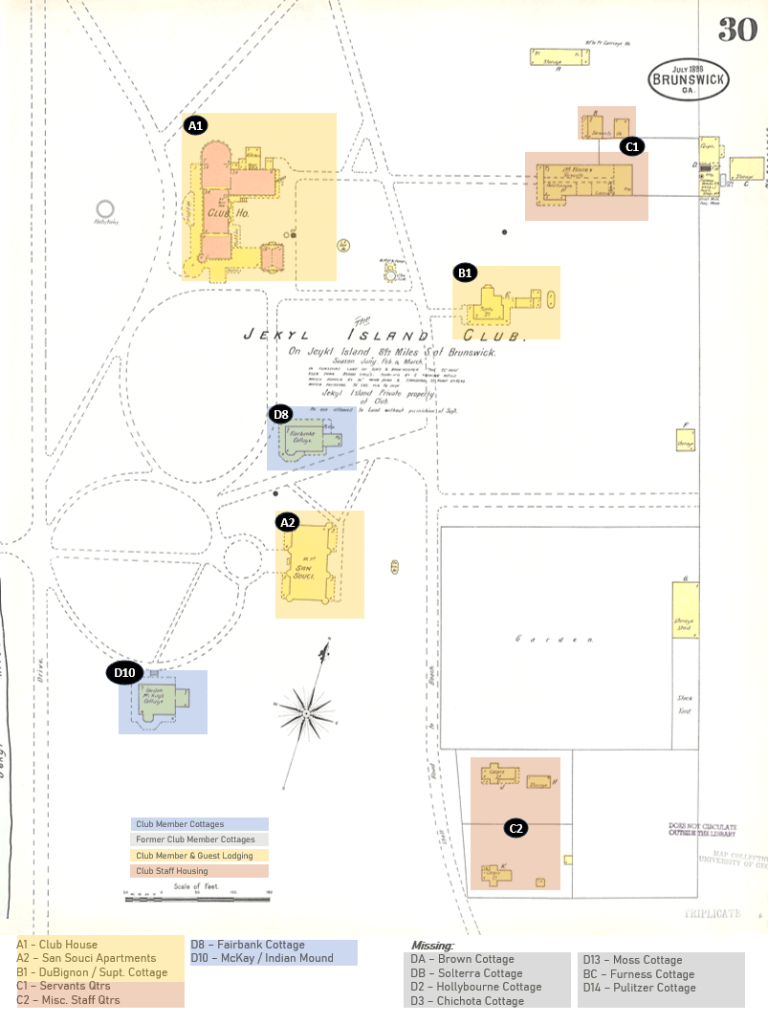

- July 1898: The relocation of the DuBignon house to allow for the construction of the San Souci apartments is reflected in the July 1898 survey map, along with the 1896 expansion of the clubhouse dining room on the north end of the building with its curved end wall, and the 1896 addition of the standalone billiard room connected by covered porches, as well as the 1896 addition of the San Souci apartments. As before, what are now seven club member cottages located to the north and south of the clubhouse district were omitted from the map with only the McKay and Fairbanks Cottages reflected in the survey map set for Brunswick.

As in the 1893 survey, lower-right of the drawing reflects what appears to be the produce gardens & club-owned structures to the southeast of the clubhouse, to include two dwellings (C2). However, by this time the new stables were likely completed and the original stables had been removed.

The early 1900’s:

- June 1908: This map was published by which time the Club’s 1901 addition of the clubhouse annex and its eight apartments beyond the billiard room with additional rooms and attic servants quarters above them as well as further additions to the dining areas on the north side of the clubhouse. Also by this time, the Fairbanks was now listed as the Ferguson Cottage, McKay was now the Rockefeller Cottage and the Porter and Goodyear Cottages were now included. Once again, none of the cottages or even the Faith Chapel built in 1904 and located to the north of the club compound were included. An inset drawing of the dynamo / power house and coal shed that was added to provide electricity to the club is also shown.

- The addition of the club-owned home provided for Captain Clark & his wife and head Club housekeeper Minnie Schuppan is shown,. However, only four of the twelve club member cottages are included on this image of the map, with Moss, Furness and Pulitzer missing to the south, and the Brown, Hollybourne, Chichota, Solterra as well as Faith Chapel and the Gould Casino are missing to the north. There is also no reference to the “Red Row” collection of housing for the club’s colored employees.

Once again, there are two club dwellings (C2) south of the produce gardens in the lower-right of the drawing. The new club powerhouse / dynamo and coal storage shed are at the top of the drawing shown as an inset as they are actually located further east than the right-hand edge of the drawing. Unlike the 1893 drawing, a club stable is no longer shown. The Brown stables are partially shown in the very upper right of the drawing, next to the sheet number 39.

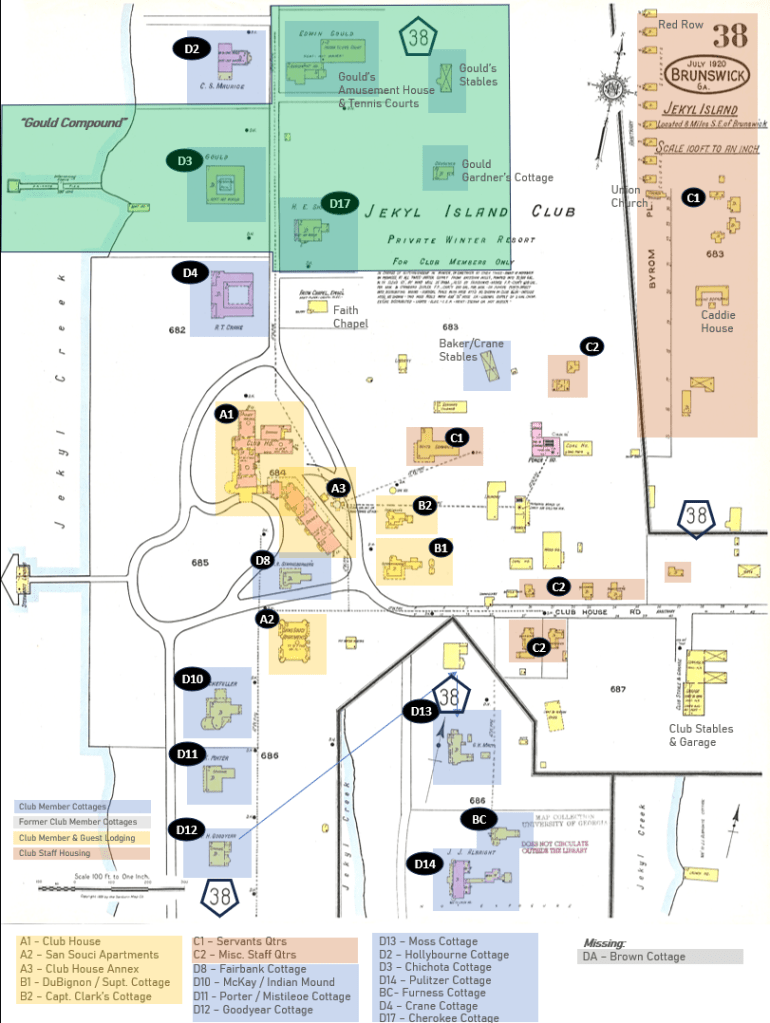

- July 1920: The first and only comprehensive survey map was the July 1920 edition, with the enlarged grand dining room added to the north end of the clubhouse and all of the still standing club member cottages, with the exception of the Brown Cottage.

- Also includes for the first time south of the Goodyear Cottage are the Macy Cottage as well as the Albright (Pulitzer) Cottage with its additions and the former Furness Cottage used for servants quarters.

- The north side of the club compound now includes the Faith Chapel and original Gould Amusement House, aka. casino, at the southwest corner of the more recently completed indoor tennis courts.

- It is noted, by this time Solterra had been destroyed by fire in 1915 and replaced by the Crane Cottage in 1918. This was well before the Jennings Villa Ospo Cottage and Frank Gould’s Villa Marianna Cottage were built.

- However, most noteworthy is the inclusion of the ‘Red Row’ community shown on the upper right corner of the map as an inset that must be re-aligned to the north end of the map; note the “38” map keys I’ve highlighted with pentagon icons.

- Red Row was created to house the club’s colored employees, noting segregation was still a normal part of life in the South until 1964.

- The name of the community came from the red Barrett’s Roofing Felt material that covered the roof and exterior of the homes.

- If it stood today, the community that was vacated in 1947 would sit southeast of the 1972 amphitheater and Jekyll Island Authority nursery off of Stable Road. The last remaining Red Row house that served as a toolshed for the JIA was razed in the 1970’s.

- The Red Row community included the ‘Negro Boarding’ / caddie’s house in its correct location. Nine of the ten single family homes that were built — No. 7 is gone, likely burned-down at some point — the commissary, recreation hall and the relocated Union Chapel that was replaced by the Faith Chapel in 1904, shortly after Red Row was established.

The two club-owned dwellings (C2) that were previously located south of the Club’s produce gardens that are now gone have been relocated and re-oriented to sit along Pier Road; the smaller dwelling labelled ‘Carpenter’ was at one time the boat engineers house and the larger, two-story dwelling labelled “Dormitory” was at one time the chauffeurs dormitory. Also included as an inset was the Club’s second of three boat houses, located along the marsh well-south of the Club’s wharf where only the concrete piers in the marsh as well as the cast iron wheel from the pulley house remain near the northern end of the bicycle path bridge leading to the historic district.

The 1930 Survey Map

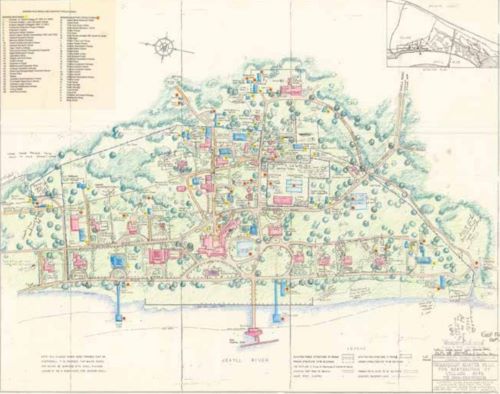

I’ve been able to find reference to the 1930 Sanborn Fire Insurance Map set for Brunswick, Georgia, as being available in “B&W Microfilm Only” instead of a scanned color-image set that would have included a sheet on Jekyll Island. However, in comparing a ‘cleaned-up version that was the basis for landscape architect Clermont Huger Lee’s Historic District restoration project in the 1960’s and more specifically, a landscape plan, I found it to be generally consistent, aside from being depicted ‘aligned ‘east up’ instead of ‘north’ as all of Sanborn’s maps were, and it is a relatively complete accounting of the club-owned structures and club member cottages in the Historic District proper.

However, Ms Lee may not have fully understood how the Sanborn’s maps used ‘insets’ with numbered alignment icons for parts of their survey that would not fit on a single page, and required readers to understand how to interpret the inserts once they were aligned with the central survey.

Ms. Lee’s restoration plan master drawing one-time appeared on the Jekyll Island Museum’s historical information kiosks entitled, ‘A Winter City’ located in front of the former Chauffeur’s dorm building at 17 Pier Road, that has since been changed.

However, it was doing further research when I discovered the map’s creator was Ms Clermont Huger Lee, who was instrumental in developing the master plan for the island in the latter part of the 1960s as part of a larger project to restore the area once known as “Millionaire’s Village” to its original state. It was likely in 1966 when Horace Caldwell, director of the Jekyll Island Authority, hired Ms. Lee as part of a team tasked with developing a plan to restore the island’s Historic District that was completed in 1968, of which her preliminary landscape plan shown below was a part. You can read more about Ms. Lee in an article that first appeared in Spring/Summer 2024, Volume 7 Number 1 of 31•81, the Magazine of Jekyll Island at the Jekyll Island Website.

I believe Lee’s illustrated plan was based-in-part on the 1920 (or 1930?) Sanborn Fire Insurance Map(s) as it seems to try and match the position of the Sanborn’s Red Row inset instead of understanding how to align the inset and shows the Caddie Lodge just north of the stables instead of near current JIA Nursery. It’s otherwise a very accurate representation of the Historic District as best as I can tell, other than the Caddie Lodge location..

As noted earlier, an illustration of the Jekyl Island Club Compound & Outbuildings, aka,, the Historic District that also cites the 1930 Sanborn map as it’ source that can be found on Wikipedia and on page 185 in June McCash’s excellent ‘The Jekyll Island Club – Southern Haven for America’s Miillionaires’. It also shows the ‘Caddie Lodge‘ in the wrong location, that is unless for some inexplicable reason someone went to the expense of moving it. Again, my intuition tells me it was merely a mis-interpretation of how insets were used on the Sanborn maps.

1920 Survey Map Composite: The following is my composite illustration of the 1920 survey map with the insets shown in their actual locations, to the north and south of the main map. The only structure from the lower insets not shown in the composite is the club’s second of three boat houses, located even further to the south along the Jekyll River and to the east of the Pulitzer / Albright Cottage. It’s noteworthy that it is the third boat house built to actually house the Club’s 84-foot, 64-ton Jekyl Island yacht built in 1896 and acquired in 1901 that replaced the smaller, 1887 Howland yacht. The Jekyl Island remained the Club’s primary yacht used by Capt. James Clark to ferry the Club’s more important guests and visitors to and from the island until it closed in 1942.

The third and largest of the Jekyll Island Club’s boat houses was located further south from the Historic District so as not to block the view of the river from the cottages that sat to the south of the Clubhouse along River Road where only the concrete house piers and the foundation and iron pulley of the ‘wheel house winch’ still remain.

The Jekyll Island Wharf and the other docks and Boathouses along Jekyll Creek Added 9 Oct 2025

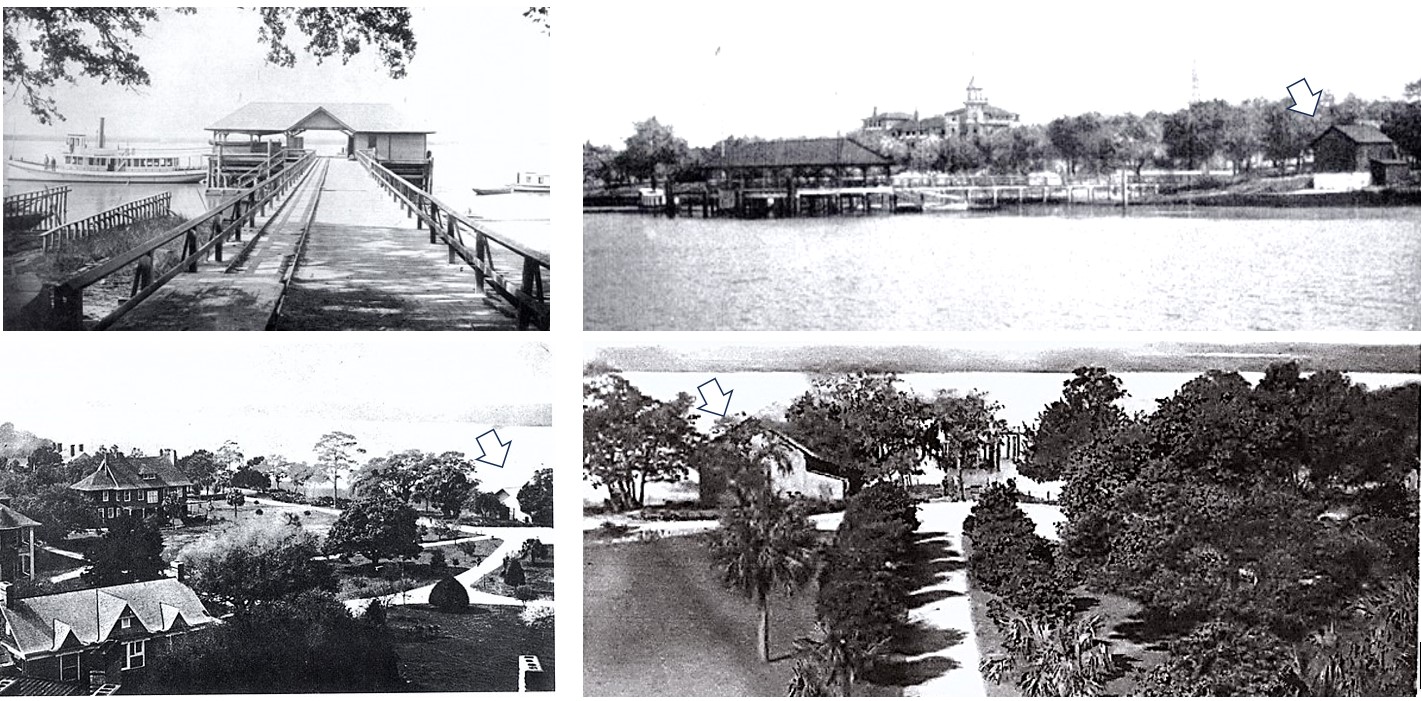

The history behind the various boat landings and boathouses along Jekyll Creek is best told in pictures, which I’ve attempted to do below by stitching together various photographs taken over time along with both a portion of Clermont Huger Lee’s 1968 Preliminary landscape restoration plan for the Historic District, and a corresponding, current satellite image of the same area along the eastern shore of Jekyll Island at Jekyll Creek.

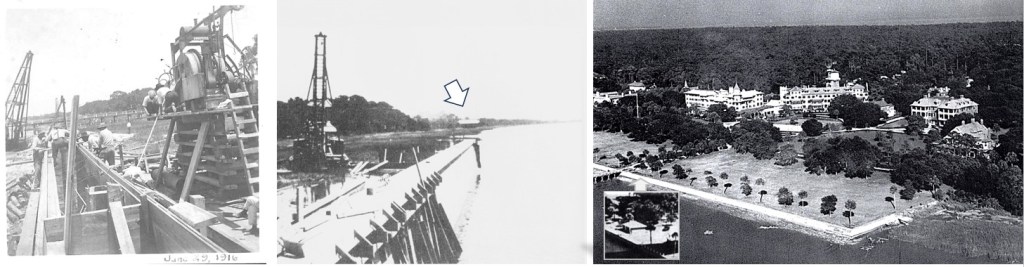

However, as a top-level timeline, the Jekyll Island pier and landing wharf inherited when the club acquired the island from John DuBignon quickly proved inadequate when construction of the clubhouse was underway in 1896 and 1897. As noted at the beginning of this section, the fixed pier and wharf had to be redesigned and rebuilt under the oversight of the clubhouse architect, Charles Alexander in 1887.

The resulting pier and wharf with it’s floating dock was utilitarian-looking vs. being finished in the more ornate victorian style used for the clubhouse. However, it provided structurally-sound and functionally sufficient to remain unchanged until 1916. Well, I say unchanged, the wharf and dock were damaged in the Hurricane of October 1898 and had to be repaired, but appears to have remained visually no different from the original 1887 design by Alexander.

As can be seen in the below photo at the upper left, by the time the first club steam yacht Howland was sold and replaced in 1901 by the 1896-built, 84-foot, 64-ton steam yacht Jekyl Island, the wharf and pier looked very much the same as it had before. However, by the early 1900’s a so-called boathouse — highlighted by the white arrows in the three other photos — had been built just south of the Jekyll Wharf at the south end of the Riverview Drive loop, just to the northwest of the McKay / Rockefeller’s Indian Mound Cottage. I say ‘so-called’ in that it did not appear to have the needed ramp or sit above the water such that it could have been used to house large, heavy craft that couldn’t be moved by animal-drawn carts.

I’ve not definitively discovered if the boathouse was built and owned by the club, or by Rockefeller who acquired the McKay Cottage in 1905 as it is referred to as both the club boathouse and as the Rockefeller boathouse in various mentions in books about Jekyll Island. The reference to Rockefeller’s boathouse came in regard to when he funded the construction of the $35,000 $1,013,600 in 2023 $’s bulkhead and seawall during the off-season summer of 1916 along the Jekyll Creek in front of his ‘Indian Mound‘ cottage — so named for the first time in February 1914 — that ran north to where the Edwin Gould ‘compound’ comprised of several lots he’d acquired from other club members began.

It’s noteworthy that after acquiring his Chicota cottage from David King in December 1900, Edwin Gould had his own, small landing wharf built in 1901 that was even longer than the club’s wharf with a small boathouse at the dock-end, and shown in the photos below.

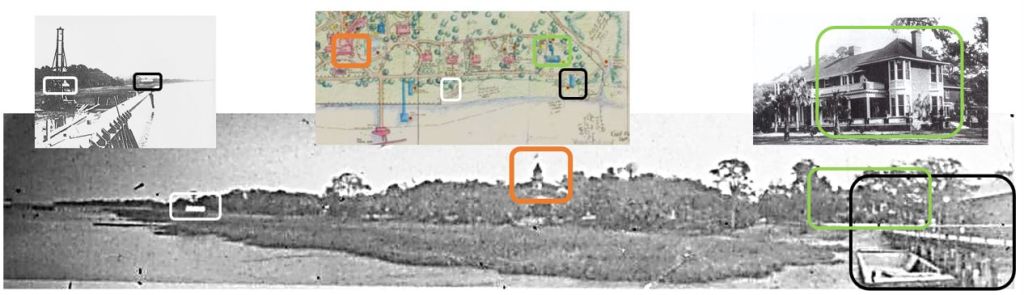

Getting back to the construction of the seawall, the club’s boathouse had to be relocated further south along the shoreline and it was moved to a location just south of the former Pulitzer Cottage, acquired by John Albright in February 1914. What I believe is mistaken by some as the larger, ~100-foot long boathouse whose concrete piers and a capstan or windless winch pulley wheel used to a haul out on a cradle mounted on a inclined slipway ramp, half-of-which was inside the boat house can be found four-tenths of a mile south of the Jekyll Pier, the club boathouse after being relocated in 1916 can be seen three-tenths of a mile south of the Jekyll Pier, where the Sunlight is reflected off its roof in the middle photo, below.

My Attempt at Lifting the Fog Around the Jekyll Island Club’s Boathouse & Historic Site

I created the following, composite image to explain why I believe the boathouse shown in these two photos — the upper right, same image as from above — and a panoramic photo likely taken from a boat sitting just off the north end of the boathouse at it’s location just south of the Albright Cottage such that it would not block views of the Jekyll Creek from any of the club member cottages. The west-face of the Albright Cottage can be made-out to the east of the boathouse in this panoramic photo.

- Black Frame: The relocated boathouse sitting 3/10th of a mile south of the club wharf, west of the Albright Cottage.

- Note that a barge, likely the club-owned barge towed by the Jekyl Island is tied up to a small wharf on the north side of the boathouse that appears to have lampposts and two people on it.

- The extent of the small wharf alongside the boathouse that extends out to the Jekyll Creek suggests that this one was truly a boathouse, likely with a rail system that allowed it to draw the smaller launches inside during the off-season.

- Green Frame: The Albright Cottage ‘peeking through the trees’ and a standalone full image.

- Orange Frame: The Jekyll Island Club’s iconic tower off in the distance

- White Frame: What I suspect is a storage shed located south of the seawall and bulkhead that was present when the seawall was under construction and razed afterwards.

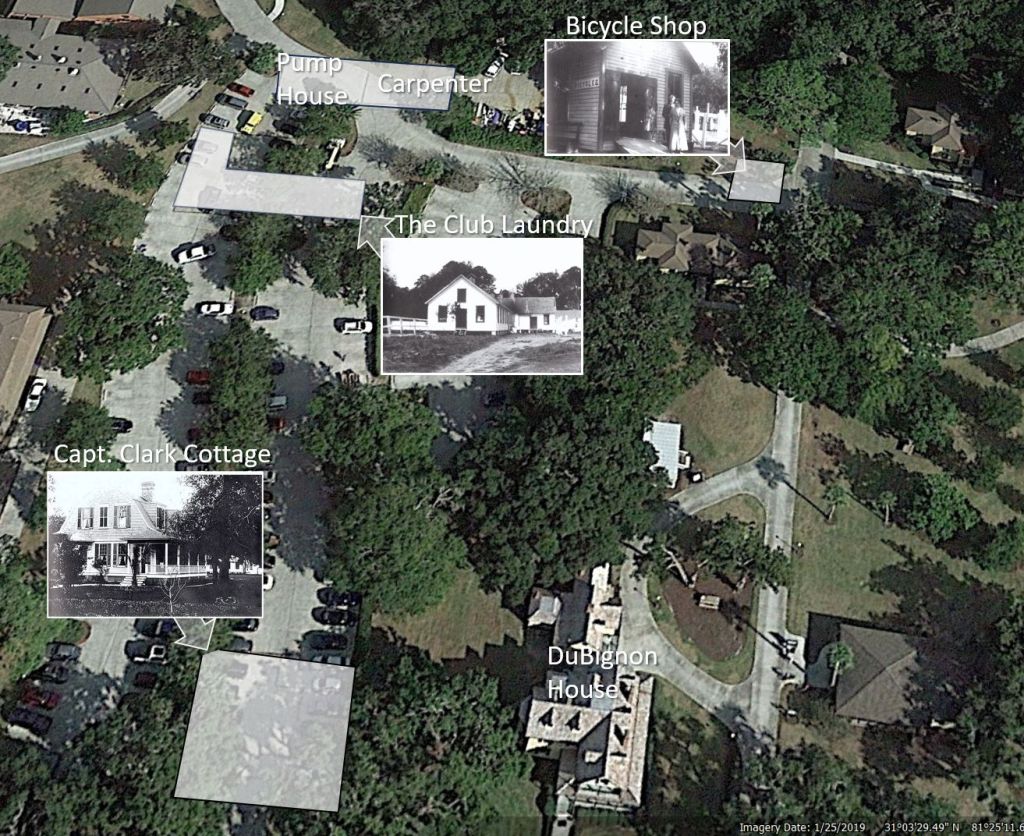

Going one step further, I’ve overlayed and annotated portion of Clermont Huger Lee’s 1968 Preliminary landscape restoration plan mentioned above with a current satellite image of the same area, noting Lee’s plan ended at the southwest corner of the historic district. The site of the club boathouse ruins is a 10th of a mile further south from there, or 0.07 tenths beyond where Lee’s 1968 map ends, just beyond the mouth of the tidal creek / canal at the threeway intersection of Riverside Drive and Stable Road. As before, I have annotated by composite map & satellite image infographic:

- Dk. Green Frame: The Gould Wharf

- Blue Frame: The Jekyll Island Club Wharf

- Yellow Frame: Original location of the club / Rockefeller boathouse

- Gold Frame: The relocated boathouse sitting 3/10th of a mile south of the club wharf, west of the Albright Cottage.

- Lt. Green Frame: Location of the larger, ~100′-long club boat house, likely built for off-season storage or maintenance of the clubs’ Jekyl Island steam yacht.

For even some additional added context on what would have been a very large boat house, I’ve created two additional composites: the first is some photos of the Jekyll Island Club’s Boathouse ruins by Mike Stroud from a previous 31•81 article which do a great job of capturing where the likely the chain-based, tabby-foundation, windless system — a capstan winch uses only ropes — was used to pull the 64-ton Jekyl Island out of the water in its railway track-mounted boathouse saddle into the boathouse. Again, it’s only a supposition, but I believe the concrete pilings were poured to handle the weight of the boathouse, not to support the rail system that the saddle was mounted to as it brought the 84-foot long Jekyl Island yacht out of the water, which would have been true for the second boathouse used to store the larger launches.

Again, I’m somewhat surprised there are no scenic photographs, nevermind more detailed photographs of the Jekyll Island Clubs’ boathouses over the years, or even boathouse operations, i.e., pulling the Jekyl Island out of the Jekyll Creek with guides alongside on the wharf’s walkway that surely existed on the last of the boathouses as it did on the boathouse that was relocated just beyond the Albright Cottage in 2016.

That said, and lacking those pictures of the actual Jekyll Island Club boathouse, I decided to create one additional composite image of the very large, recently restored 180-foot long, 22-foot wide American Boathouse in Camden, Maine, that was built in 1904 for the 130-foot long sailing yacht of Chauncey Boreland, the first commodore of the Camden Yacht Club. It should be on par with what was still being built as boathouses in the 1920’s and 1930’s, as the technology — other than replacing oxen-powered capstan and windless pull-driven systems with steam, gasoline and electric motors — would have been about the same. As before, I have annotated by composite map & satellite image infographic:

- Gold Frame: The relocated boathouse sitting 3/10th of a mile south of the club wharf, west of the Albright Cottage.

- Lt. Green Frame: Location of the larger, 100′-long club boat house, likely built for the Jekyl Island club steam yacht.

- White Dashed Line: The likely outline of the actual boathouse needed to house the 84-foot long, 64-ton Jekyl Island yacht.

- Blue Short-Dashed Line: the likely outline of the rail track system on which the saddle that the Jekyl Island sat as it was pulled into the boathouse by the Windless winch system.

- Orange Dotted Line: The likely outline of the pedestrian wharf platform used by crew members supporting the docking and winching-in of the Jekyl Island to the boathouse.

Other Maps For Points of Reference

A side-by-side view of an 1868 map of Glynn County published by the Georgia Secretary of State’s Office next to a current satellite image, annotated to show key landmarks.

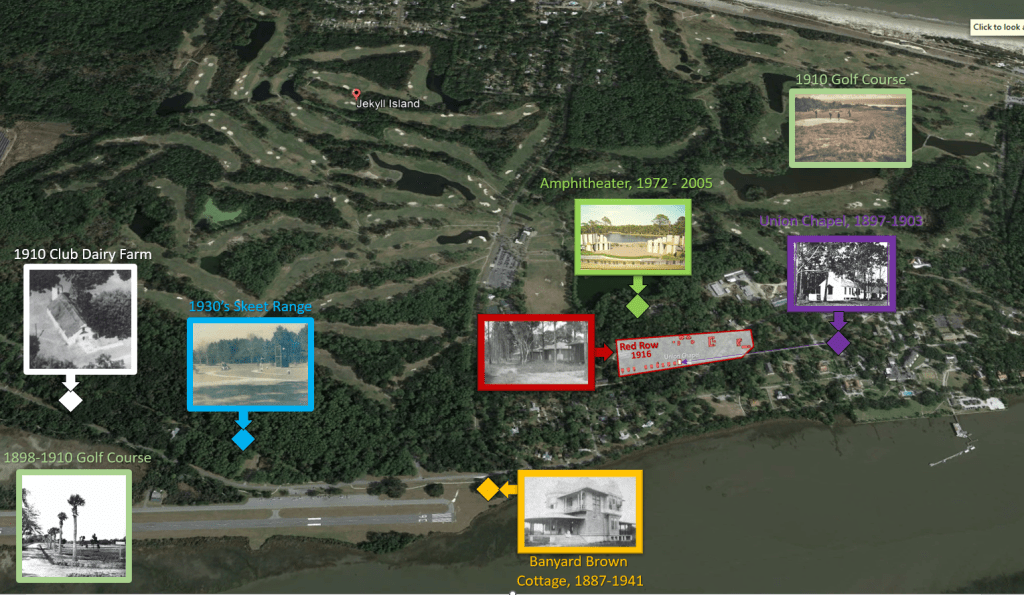

Places Lost to History: For those interested, I decided to create an overlay of a current satellite view of Jekyll Island north of the Historic District that includes the location of the Banyard Brown Cottage — at what is now the south end of the Jekyll Island airport runway — as well as where “Red Row” was located just past the Fire Department on Stable Road and north of the intersection with James road, the 1897 Union Church relocated in 1903 to Red Row, the abandoned Jekyll Island Amphitheater — built in 1972 and closed in 2005 — the Skeet Range and both the 1898 and 1910 golf courses, based on the 1920 Sanborn Survey Map and other references.

The Brick Outlines in the Historic District: At some point a brick outline of the home was added by the Jekyll Island Authority in the post 1947 parking lot to the north of the DuBignon house to represent where the Fairbank Cottage and other long-since demolished structures were located.

The First Owners of the Club Apartments: The following is something I created based on two illustrations that were included in Anna Ruth Gatlin, Ph.D and Melissa Gatlin’s excellent ‘A Guide to the Historic Jekyll Island Club – Walking Tour of the Island’s Rich History and Architecture’ that I wanted to include in my own Jekyll Island retrospective, but that I didn’t want to copy and that may have somehow swapped the names of the 1st and 2nd floor apartment owners, based on other sources I’ve found. Again, another set of details I need to further investigate.

More about the Sanford Fire Insurance Maps

The Sanford Fire Insurance maps, “…were designed to assist fire insurance agents in determining the degree of hazard associated with a particular property and therefore show the size, shape, and construction of dwellings, commercial buildings, and factories as well as fire walls, locations of windows and doors, sprinkler systems, and types of roofs. The maps also indicate widths and names of streets, property boundaries, building use, and house and block numbers.”

It’s also been noted that the maps, when updated with a regular rhythm, provided historians and officials with a ready reference for when and how towns and cities developed and expanded over-time, including major changes such as the creation of roads and clearing of land or existing developed land and structures to further development and growth.

As to their demise:

“More specific reasons for the decline in use of Sanborn maps were supplied by a librarian for the Insurance Company of North America. “As the nation grew in all areas,” she wrote, “keeping the maps up to date became cumbersome, time-consuming, and expensive. At the same time, increased financial strength of the Company and the progressive reduction in the number of instances in which we needed such detailed locality information led us to discontinue the service prior to 1950. No comparable source of data has replaced use of maps at INA. There is no need to maintain wealth of detail about the small risk to forestall the possibility of catastrophe from fire. Inspection services maintained by fire insurance rating organizations and our own inspection services have proved adequate in the light of modern building construction, better fire codes, and improved fire protection methods.”

For those unfamiliar with the history of firefighting and fire insurance, it’s a fascinating subject given the major fires that plagued densely-populated urban cities in the 1800’s when so much was built of wood, illuminated by oil lamp flames, heated by open fire or coal-fired systems and then, in the 1880’s, began to incorporate “electrified” systems that had not yet been time-proven for their durability and safety.

This was at a time when home and building owners in many places in the United States had the option of paying a fire-protection subscription in advance to professional firefighting companies which was a large source of their funding for preferential attention. Volunteer fire companies were quite common and often times fire insurers contributed money to these departments and awarded bonuses to the first fire engine arriving at the scene of a fire. The downside to some of these practices was the implied belief — real or imagined — that if a fire broke-out in an uninsured structure, the fire company might not even bother to respond or extinguish it, unless it was threatening an insured, neighboring structure or home. It was a practice used in Europe and Benjamin Franklin brought the practice into fashion in the U.S..LIBRARY OF CONGRESS COLLECTION

Links to Other Parts of This Series

- Jekyll Island & The Jekyll Island Club: Introduction & Index

- Jekyll Island: Pre-Colonial to the Pre-Club Era, 1500 to 1883

- Jekyll Island: The Jekyll Island Club Era, 1883 to 1947

- Jekyll Island: The State Era and Now, A Photo Collection (Future)

- Sanborn Fire Insurance Maps: Jekyl Island